In a child’s imagination, a climbing frame can become a pirate ship or a princess’s castle. But during this summer’s heat waves, the Sahara desert and the surface of Venus might be the playground fantasies that come to mind. In Denver last month, a toddler got second-degree burns from walking barefoot for less than two minutes across a rubber playground surface that reached 160 degrees.

August 14th, 2023

Courtesy of The Washington Post, a report on the impact of urban heat on playgrounds and some green solutions to help cool things down:

As monkey bars and bucket swings get hot enough to hurt in our warming world, kids are running out of places to play safely. Rather than despair or default to screen time, parents should use baking playgrounds to introduce important lessons in climate resilience and citizenship. They can explain why it’s too hot to play and help their kids ask schools, school boards and city councils for more shade at existing playgrounds and better designs for new ones.

Playgrounds are vulnerable to overheating for two key reasons. They’re often made of materials that retain a lot of heat, and they lack shade.

Popular rubber surfaces were developed as part of efforts in Germany in the 1960s to repurpose worn-out tires rather than send them to landfills. In theory, they keep kids safer, cushioning eager climbers and giving speedy sliders a softer landing.

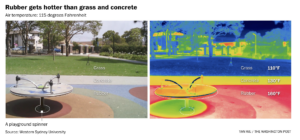

Unfortunately, those rubber floors and their substitutes, such as artificial turf, can get very, very hot. Between 2019 and 2021, researchers at Western Sydney University in Australia — a country that has a lot of experience with intense heat and ultraviolet exposure — visited playgrounds to measure the surface temperatures of flooring material and play equipment. Many of their measurements were taken on extremely hot days, but on an 86-degree day, rubber mulch and artificial turf reached 167 degrees Fahrenheit, proof that even on tolerable days, playgrounds can get dangerously hot.

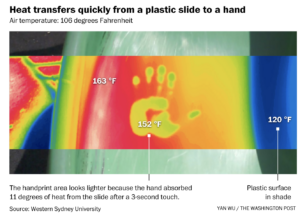

Other equipment can trap heat, too. Metal bars and frames pose an obvious risk. But the Sydney researchers were also struck by a rubber dolphin apparatus. The surface of this piece of play equipment reached a temperature of 197 degrees, while some black swings got as hot as 180 degrees. At those temperatures, children could burn their legs and hands in just a few seconds — like the Denver 2-year-old did.

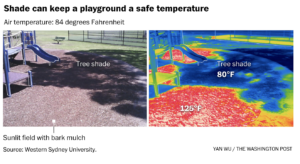

One easy solution is sun protection. Unfortunately, many playgrounds have little or none. When researchers looked at 174 elementary schools in the St. Louis area for a 2019 study, they discovered that poorer students had much less shade cover in their playgrounds. A survey in New Zealand that same year found that 60 percent of playgrounds had no shade at all.

And kids are particularly vulnerable to heat. Their bodies are less adept at temperature regulation than adults’ and they may be less likely to seek shelter or drink water of their own accord. They breathe more often than adults do, meaning they absorb more pollution on days that are both hot and smoggy. And childhood UV exposure might mean greater cancer risk in adulthood.

If playground designers and the people commissioning them don’t start taking heat and shade into consideration, the resulting spaces will, the Australian scientists wrote, “be too hot for children to use.” A group of American professors who looked at 100 playground spaces across the United States deemed many in a 2019 study “unsuitable for any form of play or leisure.”

The good news for children and parents is that simple steps can make playgrounds, and their neighborhoods, more pleasant and usable. And playground designers are, more than many adults, interested in what kids have to say.

Shade can come from trees, such as the ones the Toronto District School Board started planting at schools in 2007. They also suck carbon dioxide from the air.

Other options include sun sails that shade playground equipment and surfaces, including while saplings are growing. Even switching the color of playground materials can make a difference. White concrete tends to be cooler than red brick; yellow rubber is better than black. And design trends toward giving children contact with nature even in human-created spaces are bringing water to play spaces and elevating materials like wood that are less likely to cause burns.

Playground architects are increasingly soliciting children’s input, as my colleague Caitlin Gibson reported earlier this year. If those adults can build the dragon or butterfly of a kid’s dreams, they should also consult children on how to keep them cool, too.

Funding for playgrounds is often allocated on the local level. So kids and their families should call upon school board or city council meetings to include shade and safe materials in budgets and bidding processes.

“We need to treat kids not only as victims, but as problem-solvers … not only as consumers, but as citizens,” University of Melbourne pediatrics professor Ann Sanson told a panel on children and climate change earlier this year, at the International Congress on Evidence-Based Parenting Support. After all, action is an antidote to anxiety.

Transforming the playground could be just the beginning for little lobbyists. Next up might be demanding solar panels on the school roof, a gym that can act as a cooling station in heat emergencies or a food-waste-management program operating out of the cafeteria. If children are supposed to build a better world, let them start by fixing the spaces intended to let their dreams take flight.

'Black Swans' are highly improbable events that come as a surprise, have major disruptive effects, and that are often rationalized after the fact as if they had been predictable to begin with. In our rapidly warming world, such events are occurring ever more frequently and include wildfires, floods, extreme heat, and drought.

'Green Shoots' is a term used to describe signs of economic recovery or positive data during a downturn. It references a period of growth and recovery, when plants start to show signs of health and life, and, therefore, has been employed as a metaphor for a recovering economy.

It is my hope that Black Swans / Green Shoots will help readers understand both climate-activated risk and opportunity so that you may invest in, advise, or lead organizations in the context of increasing pressures of global urbanization, resource scarcity, and perils relating to climate change. I believe that the tools of business and finance can help individuals, businesses, and global society make informed choices about who and what to protect, and I hope that this blog provides some insight into the policy and private sector tools used to assess investments in resilient reinforcement, response, or recovery.