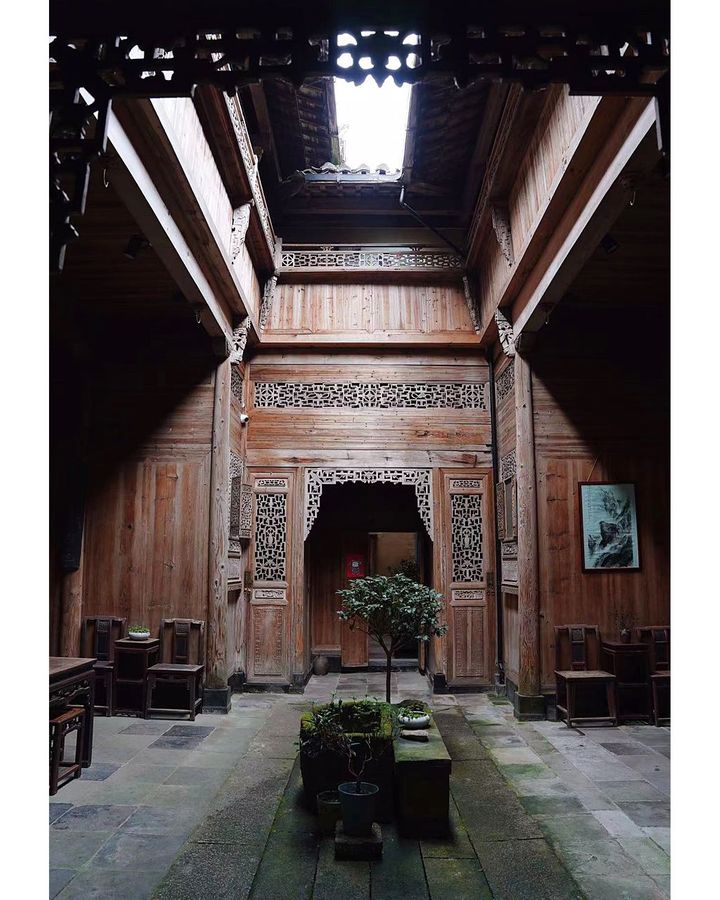

Ru Ling loves spending time in skywells. To her, these courtyards of old Chinese houses are the perfect place to be in on a hot and humid day.

“They are airy, cool and well-shaded,” says 40-year-old Ru.

From 2014 to 2021, Ru lived in a century-old timber-framed home in the village of Guanlu in eastern China’s Anhui province. She moved there for a change of life after living and working in air-conditioned buildings for many years.

“The natural cool feeling of my home in summer was so refreshing, and a rare find in the modern world,” she says. “It also gave the house a calming and zen vibe.”

Ru says that the house’s skywell helped create this cooling effect. And she’s not alone in extolling the benefits of skywells in hot weather. Studies have found that the temperatures inside some of the skywells in southern China are significantly lower than the outside – by up to 4.3C.

In today’s rapidly urbanising China, fewer and fewer people live in skywell dwellings – air-conditioned flats in multi-storeyed buildings and tower blocks are the main forms of homes.

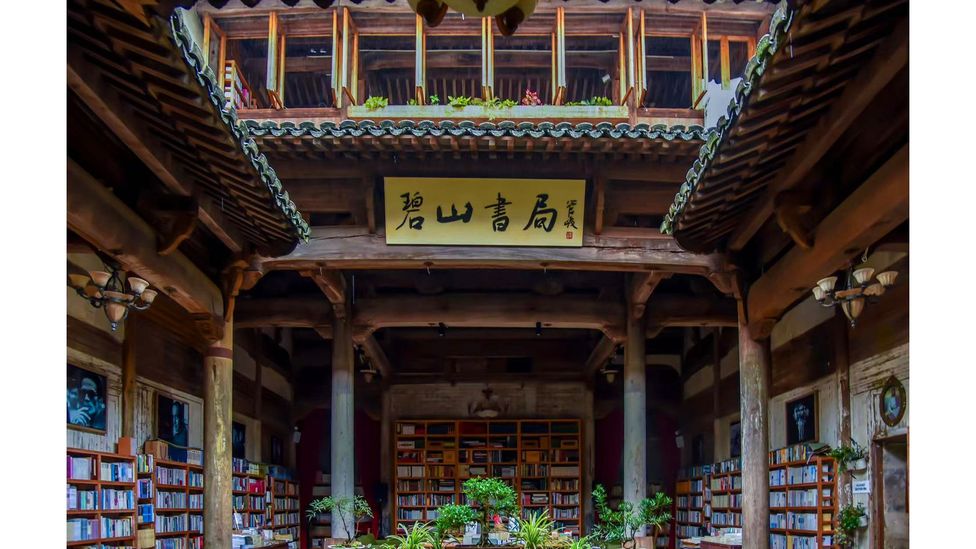

But a revival of interest in traditional Chinese architecture is leading some of historic buildings with skywells to be restored for modern times. Meanwhile, as a government push has made low-carbon innovations in the building sector a trend in the country, some architects are drawing inspiration from skywells and other traditional Chinese architectural features to help keep new buildings cooler.

In a bid to help keep modern buildings cool, architects are drawing inspiration from skywells (Credit: Wuyuan Skywells Hotel)

A skywell, or “tian jing” (??) in Mandarin, is a typical feature of a traditional home in southern and eastern China. Different from a northern Chinese courtyard, or “yuan zi” (??), a skywell is smaller and less exposed to the outdoor environment.

They are commonly seen in homes dating to Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, which were designed to house different generations of relatives, according to a 2010 paper published by the Journal of Nanchang University in China.

Although a skywell’s size and design vary from region to region, it is almost always rectangular and located in the core of a house. It is either enclosed by rooms on four sides or three sides plus a wall. Some large houses have more than one skywell.

They are relatively common in historic residences in large swathes of southern and eastern China, such as Sichuan, Jiangsu, Anhui and Jiangxi. Some of the best-preserved can be found in Huizhou (??), a historical region that spreads between modern-day Anhui and Jiangxi.

Skywells were designed to cool buildings in an era well before air-conditioning existed. When wind blows above a skywell house, it can enter the indoor space through the opening. Because outdoor air is often cooler than indoor air, the incoming breeze travels down the walls to the lower stories and create airflows by replacing warmer indoor air, which rises and leaves through the opening.

Yu Youhong, 55, has spent more than 30 years restoring skywell homes in Wuyuan county of Jiangxi province, a part of the old Huizhou. As an inheritor of intangible cultural heritage recognised by China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism, he has obtained a wealth of knowledge about skywells.

The main purposes of a skywell, he says, is to allow in light, improve ventilation and harvest rainwater. In Huizhou, a skywell is small but tall, and the rooms around it can block out sunlight on hot days, enabling the bottom of the skywell to stay cool, he adds.

Meanwhile, hot air inside the house can rise and escape through the opening above the skywell, which “works just like a chimney”.

“The ground floor of old Huizhou houses normally have very high ceilings and face towards the skywell directly, which is good for ventilation,” Yu says. “Some wealthy families had two or even three skywells, enabling them to have even better ventilation.”

Hot air inside the house rises up and escapes through the skywell opening, which acts like a chimney (Credit: Ru Ling)

Although skywell buildings have existed in China for hundreds of years, in recent times they have often been forgotten by people who prefer modern facilities. Over the past two decades, however, due to a revival of traditional Chinese architecture, part of a broader resurgence of traditional Chinese culture, skywell buildings have been making a comeback.

One of the skywell homes restored by Yu is in the village of Yan, in Wuyuan county. The once-derelict 300-year-old house was bought by Edward Gawne, a former marketing director from the UK, and his Chinese wife, Liao Minxin, in 2015. The couple turned the three-storey house into a 14-room boutique hotel with the help of Yu.

Although Gawne and Liao had air-conditioning fitted in all their guestrooms, they kept the communal spaces surrounding the skywells in their original status: unsealed and with natural airflow. Gawne says that even without air conditioning the skywell areas are very comfortable in summer. “Everyone notes when they step into the house how naturally cool it is.”

Yu says he expects skywells, as an architectural feature, to be “more and more popular” among younger generations because of their ventilation and lighting functions, especially as sustainability becomes an important element for new buildings.

Even when there is no natural wind, air circulation still takes place inside a skywell home due to the “chimney effect”. The temperature difference between the top and bottom of the skywell means warm air inside the skywell rises, drawing cooler air from the rooms to the bottom of the skywell.

Traditional skywell homes further south in Lingnan (??), a historical region consisting of the modern-day Chinese provinces of Guangxi, Guangdong and Hainan and what is now northern and central Vietnam, have smaller and deeper skywells than other areas due to the longer and hotter summers.

As a transition space between indoor life and the outdoor environment, a skywell acts as an effective heat buffer to shield residents from the hot air outside. But the largest part of skywell’s cooling effect actually comes when there are bodies of water in the enclosure.

Evaporated water cools hot air, a process known as evaporative cooling which is well-reflected in Huizhou skywells. In the past, Huizhou families collected rainwater in their skywells because they believed such an action could safeguard and boost their wealth.

Skywells here therefore have channels around them to drain rainwater coming from the roofs. According to Yu, some wealthy families had a drainage system dug under the skywell to ensure that rainwater would only leave the house after circumnavigating the front hall under the ground.

Huizhou skywells also have a large stone vat in the middle to hold water for daily use and to put out fires.

A 2021 study of skywell dwellings in two traditional Huizhou villages found that evaporative cooling was likely the main reason that average temperatures inside the skywells were 2.6-4.3C lower than the average external temperatures.

Skywells act as a heat buffer, shielding residents from hot outside air (Credit: Zhou Jie)

Today, government directives are starting to play a key role in the return of skywells in modern buildings. Since 2013, the Chinese central government has been pushing for green buildings which save resources and emit less pollution in their entire lifecycles. A 2019 government instruction required that 70% of buildings completed in 2022 should meet its “green” standard, which includes a series of specific criteria, including how good a building’s insulation is and how environmentally-friendly the building materials are.

Architects are now looking towards the principles behind skywells while designing new buildings to save energy. One example is the National Heavy Vehicle Engineering Technology Research Centre in the eastern Chinese city of Jinan. The 18-storey glass-walled tower block, completed last year, has a giant interior skywell in the middle, which stretches from the fifth to the top floor. The elevators, toilets and meeting rooms are all situated around this shaft, which helps improve the lighting and ventilation of the centre and reduces the overall energy consumption, the architects, from the Shanghai-based CCDI Group say.

CARBON COUNT

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

In the county of Jixi in Xuancheng, a part of historic Huizhou, the site of the former town hall was revamped in 2013 to be a museum. The complex pays homage to its surroundings of Huizhou-style architectures by having several skywells, which it says brings airflow to the inside and helps to preserve several ancient trees on the site.

Meanwhile, a popular tourist village in Sichuan – a province known for its hot and humid summer – has a series of round houses with skywells and large eaves.

Some skyscrapers use the ventilation principle of skywells to improve airflows without building a courtyard out of concerns of practicality. The 68-storey Dongguan TBA Tower in Guandong province, for example, brings natural airflows to every floor with internal “windpipes” that function in a similar way to skywells. The tower’s general manager told a local newspaper that the aim is to keep the building’s temperature comfortable in spring and autumn, using only natural ventilation.

The National Heavy Vehicle Engineering Technology Research Centre in the eastern Chinese city of Jinan features a giant skywell (Credit: CCDI Group)

Ancient “green wisdom” such as skywells continue to inspire today’s climate adaptive design and innovations in passive cooling, according to Wang Zhengfeng, a postdoctoral researcher in environmental humanities at the Institute for Area Studies at Leiden University in the Netherlands who previously trained as an architect. Passive cooling is a method that incorporates design and technology to cool a building without the use of power.

However, Wang points out some challenges for bringing skywells into modern designs. The mechanisms of courtyards facilitating natural lighting, ventilation and rain collection are well known, but applying these principles needs to be site-specific, she says.

Because traditional skywells had different shapes, sizes and features, which were highly dependent on their natural surroundings – for example, how much sunlight or rainfall there was in the region – adding skywells into modern buildings requires designers to be sensitive to their project’s context and situation, making it difficult to apply them as a universal solution, she explains.

“Meanwhile, artificial lighting, air conditioning and water supply have become so readily available that we depend on them with little regard for the environmental cost,” she adds. “It won’t be easy to be sustainable by learning from the past without reflecting on our current behaviours.”

When asked about why skywells have caught more attention of modern Chinese people, Wang says that the courtyard is also designed to serve as a gathering space for families or communities, and comes with ritual meanings. “Perhaps changes in the way of life could also trigger vernacular nostalgia among people living in concrete and glass forests.”