When it comes to blistering metropolitan temperatures, New York has the worst existing conditions — known as urban heat island effects — relative to any other major U.S. city.

That’s the takeaway from a new analysis by the research nonprofit Climate Central, which looked at 44 large cities and their potential for trapping heat. But environmental experts said there are short- and long-term solutions that neighborhoods can employ to cool off their communities, from tree plantings to implementing building codes that prioritize ventilation or reflective paint.

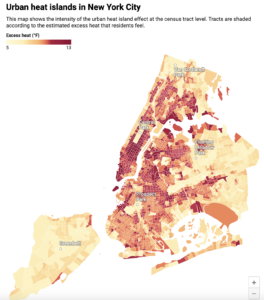

The team examined nearly 19,000 census tracts, and for each one it calculated what’s known as an urban heating island index. This number is a validated indicator of how much hotter a city is than if it were a natural greenspace like a field or forest, which theoretically would have roughly a zero index. Population density, tree cover, greenspaces, the amount of paved surfaces, greenspace availability, human activity, building heights and materials were among the factors used to pinpoint urban heat islands, or areas that were hotter than average. The researchers then calculated how much hotter a city can get, both overall and by individual communities.

According to Climate Central, the Big Apple’s iconic concrete and steel skyscrapers and more than 6,000 miles of asphalt absorb and radiate enough heat to make New York City at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit hotter. It’s one of nine major metropolises with this distinction. Heat waves in places such as Phoenix might burn a person’s exposed feet, but extra warming in mega hubs like New York City can expose way more people to heat stress due to population density.

These elevated temperatures affect roughly 80% of New Yorkers, or just over 7 million people, according to the study. New York City had the greatest number of people exposed to the urban heat island effect, but this peril varied from neighborhood to neighborhood. On a hot day, it can feel more than 10 degrees hotter for about 40% of the city’s population because of the disproportionate amount of built environment.

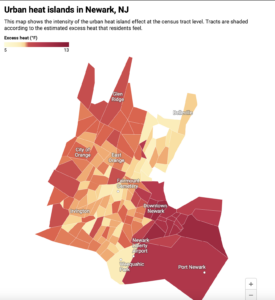

Jen Brady, a research manager at Climate Central who co-led the study, was not too surprised by New York City’s potential for urban heat islands, but was caught off-guard by what they found in Newark, New Jersey. Its population is far less than New York City’s, and even has less skyscrapers, but its ability to expose urbanites to extra hot conditions was almost on par with New York City.

“It’s not that New York is just off the charts in every way than other cities, it’s that you have to go further out of the city to get away from the really intense spots,” Brady said.

What makes New Jersey’s largest city more than 11 degrees hotter is its enormous port – a vast and flat concrete desert. A 2023 list that was compiled by Lawn Love, a national landscaping company, ranked American cities for their greenery, with Newark coming in last place. The New York City-Newark area’s three airports also contribute to the urban heat effect.

“The urban heat island really creates a very dangerous heat environment for New Yorkers and that it’s not equal across the whole city is validated in this study,” said Sonal Jessel, director of policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice.

Why NYC and Newark are the twin cities of heat islands

Urban heat islands are not directly tied to climate change, but the gradual, human-caused baking of the Earth can fuel metro health crises during the summer months — exacerbating heat exhaustion and increasing fatalities. The city’s cooling centers remained closed through mid-July despite a spike in heat-related emergency room visits, and researchers said this week that the recent national heat wave would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change.

“Urban areas are hotter, and if the overall temperature goes up and you’ve got more and more extreme heat waves, that’s going to compound the challenge,” said Dr. Kristie Ebi, a professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Health and the Global Environment.

Heat islands are also due to more than just the building materials absorbing solar radiation — it’s also about the heat contributed by human activities such as traffic, air conditioners and industries all expelling excess heat into the air.

Those attributes are not spread evenly around New York City, Newark and metro hubs, leading some neighborhoods to be more dangerous than others. The hottest areas tend to be home to people with lower incomes and people of color.

NYC’s coolest areas are the ones with the least amount of manmade materials and the most greenspace, especially trees. Spots like Central Park and most of Staten Island had a heating potential of 5-7 degrees hotter in Climate Central’s study.

Commercial and industrial parts of the Bronx, Midtown and Lower Manhattan were as much as 13 degrees hotter than the norm. Coast through Central Brooklyn on a hot day, and one will find that temperatures are a few degrees cooler in places like Park Slope and Cobble Hill than in nearby Gowanus or Bed-Stuy.

These disparities are common among American cities. Even for a much smaller urban area like Newark, which is home to roughly 300,000 people, lower-income sections tend to run hot as well. About a quarter of Newark’s residents live in poverty. Some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods — like the northern region of the Ironbound neighborhood, where 40% of residents live in poverty according to census data — are also among the most impacted by the urban heat island effect, the study estimates.

“The world is getting hotter [from climate change], and the urban heat island effect is just making that problem worse for certain people,” Brady said. “That’s where we see a lot of the disparity in these communities that are not only hotter, but there’s no escape from it – you can’t just go to the park at the end of the street because the park at the end of the street doesn’t exist.”

Mapping out the heating differentials between sections of town can also guide communities and local governments on where solutions are needed most. Ebi said cooling down NYC will require expensive and long-term changes to the way urban infrastructure is built, including code changes that require more building ventilation and reflective or green roofs. Climate change measures are key, too, and in January, Local Law 97 compliance begins, whereupon large NYC buildings must limit their annual greenhouse gas emissions.

“As you think about your urban plan, think about are there places where you could put in pocket parks. Are there any kinds of ways to green a city so that there’s more trees?” Ebi said.

In 2021, the Nature Conservancy estimated that NYC is home to 7 million trees, which provides about 22% canopy cover citywide. But broad disparities exist between boroughs and neighborhoods — both in terms of existing trees and planting in recent years. The City Council has called upon the parks department to increase the city’s tree canopy to 30% by 2035. As Gothamist reported, new tree plantings last summer and fall plummeted to the lowest rate seen in 15 years.

Other inexpensive and effective solutions include painting buildings white to reflect the sun, the way it’s been done for centuries along the Mediterranean Sea in countries such as Greece.

“We are in a warming world,” Brady said. “These solutions really will work anywhere, like planting trees, making more green space, making more impervious surfaces.”

Another option would be radically altering the daily human schedule to lower health risks – a solution that has been employed by societies that have confronted severely hot temperatures for centuries. A modified work schedule in Latin American and African countries usually has a break during the hottest period of the day, which is the afternoon. Outside work or leisure time may happen in the evenings or begin during predawn hours and end by the afternoon.

“They [Latin America] have been exposed to it [extreme heat] for generations, and so they modify their work schedules,” said Dr. Uwe Reischl, a public health professor at Boise State University. “We might think of having to adopt some of these principles as well so that during the hardest part of the day, maybe people should relax.”