December 15th, 2023

Via the Water Education Foundation, an article on how Colorado River shortages are driving major advances in recycled sewage water use in the western U.S.:

After more than two decades of drought, water utilities serving the largest urban regions in the arid Southwest are embracing a drought-proof source of drinking water long considered a supply of last resort: purified sewage.

Water supplies have tightened to the point that Phoenix and the water supplier for 19 million Southern California residents are racing to adopt an expensive technology called “direct potable reuse” or “advanced purification” to reduce their reliance on imported water from the dwindling Colorado River.

“[Utilities] see that the river is overallocated, and they see that the climate is changing,” said Kathryn Sorensen, former director of Phoenix Water Services Department. “They’re looking at this and understanding that the river supply is highly variable and extremely uncertain in the future.”

The Colorado River that sustains nearly 40 million people and more than 4 million acres of cropland across seven states is shrinking because of climate change and overuse. The river’s flows have declined approximately 20 percent over the past century, and a more than two-decade drought that began at the turn of this century has pushed the system to its limits.

“We can’t be dependent on hydrology, we have to manage our own fate.”

~Adel Hagekhalil, Metropolitan Water District’s general manager

With so much at stake, cities dependent on the river are strengthening water conservation measures and pursuing new sources of water with urgency.

Phoenix is quickly advancing plans to purify its wastewater for household use in the expectation of state regulators’ approval.

The city’s water agency is drafting blueprints, securing funding and crafting communication strategies to assure customers that drinking recycled water is safe and necessary in the face of prolonged droughts and climate change.

Communities in California could see a major advance in wastewater reuse as soon as next Tuesday (Dec. 19). State regulators that day are expected to adopt rules that will allow cities for the first time to pipe highly purified sewage water directly into drinking water supplies.

Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has plans well underway to build one of the world’s largest wastewater purification plants. It expects to release the project’s environmental review next year.

“We can’t be dependent on hydrology, we have to manage our own fate,” said Adel Hagekhalil, Metropolitan’s general manager. “The future is about recycling and reuse.”

At full scale, Metropolitan’s plant would produce 150 million gallons of purified water each day, enough for roughly 400,000 Southern California households.

On Shaky Ground

Finding a new local, reliable water supply is critical for Arizona as more than a third of its water comes from the over-committed Colorado River. The search has become more pressing in recent years as Arizona has sustained cuts to its river supply.

Under a drought deal with other states that rely on the river, Arizona this year took a 21 percent reduction – or about six times the amount of water the city of Tucson uses annually – with another round of cuts looming next year.

The inconsistent river supply is a major concern for Phoenix, the state’s most populous city and its capital. Though Arizona farmers and tribes bore the brunt of the recent Colorado River reductions, there’s a chance future cuts will be spread to cities under the next set of river operating rules that take effect in 2027. The revisions are under negotiation by the federal government, Mexico, tribes and the seven Western states that use the river.

The Phoenix metropolitan area has grown rapidly over the last 23 years despite the drought, augmenting its river supply with groundwater. But the underground stores alone won’t sustain the region. Groundwater is also in great demand. Earlier this year Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs halted new permits for homes planned in areas of the state where groundwater is the only source of potable water.

“I will not bury my head in the sand, cut corners, or put short-term interests over the state’s long-term economic growth,” Hobbs said of her decision last June.

A Drought-Proof Source

Phoenix, the nation’s fifth-largest city, believes it can replace some of what it draws from the Colorado River and pumps from underground by recycling water that’s flushed down sinks, showers, toilets and washing machines.

Arizona for decades has been cleaning wastewater from households and businesses and using it to water golf courses, cool nuclear power plants and recharge aquifers. But until 2018, state law prohibited utilities from putting recycled wastewater directly into drinking water. Lawmakers, aware that Arizona was facing cuts to its Colorado River supply, lifted the prohibition to allow cities to pursue treated wastewater as a drinking source. The state’s drinking water regulators are drafting rules that will allow cities to adopt the technology.

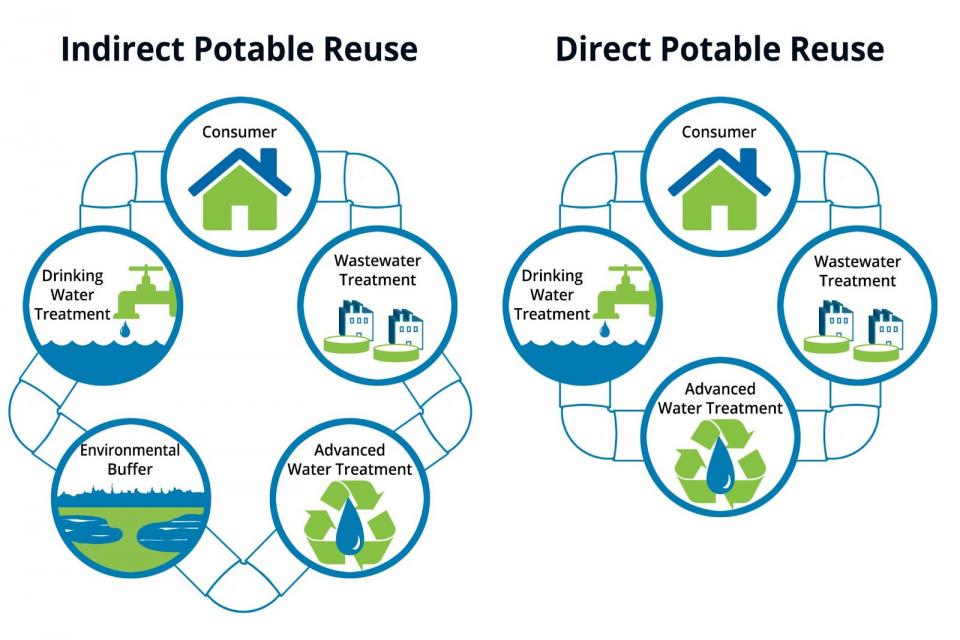

The allure of direct potable reuse or “advanced water purification,” is its ability to quickly get highly treated wastewater into the drinking water supply. The method treats wastewater through a three-step purification process involving membrane bioreactors, reverse osmosis and ultraviolet light disinfection and adds it to a drinking water source without going through an environmental buffer.

The method also promises to be energy efficient. A 2021 study found that putting recycled water directly into the water supply requires far less power than long-distance water transfers or seawater desalination.

A more widely used water recycling method known as “indirect potable reuse” requires treated wastewater to first go through an environmental barrier such as an aquifer where it is filtered naturally through layers of sand and gravel. The water is then pumped from the ground and treated again before entering the drinking water supply.

Orange County pioneered the technology in the early 1970s to increase its drinking water supply and replenish aquifers along the Southern California coast as a barrier to seawater intrusion. The county water district operates the world’s largest plant of its kind.

“This is a sustainable resource that keeps coming to us in the form of wastewater.”

~Nazario Prieto, assistant director of Phoenix’s wastewater division

Direct potable reuse has been used sparingly in parts of rural Texas, but Phoenix is looking to do it on a mass scale. And the city is wasting little time: The Phoenix City Council recently committed $30 million toward retrofitting a shuttered water recycling operation for advanced purification, even though Arizona regulators have yet to finalize rules for the technology.

Nazario Prieto, assistant director of Phoenix’s wastewater division, said the closed Cave Creek Reclamation Plant in north Phoenix is a perfect candidate for direct potable reuse as it’s near a facility that treats Colorado River water. A short pipeline could connect the two plants, allowing the recycled product to be blended with the Colorado River supply.

“This is going to play a big role in our water resources portfolio, especially with the uncertainty on the Colorado River,” Prieto said. “Water’s precious here in the desert and this is a sustainable resource that keeps coming to us in the form of wastewater.”

Phoenix is also exploring the construction of a larger, regional wastewater plant to serve Scottsdale, Tempe, Glendale, Mesa and other cities in the metropolitan area. A regional plant would be able to treat up to 80 million gallons of effluent per day and if built to full capacity, the regional and Cave Creek plants combined could supply about 20 percent of Phoenix’s yearly potable water needs.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality expects to issue final direct potable reuse rules by the end of 2024 and begin accepting applications for permits in 2025. It estimates recycled water could stream out of taps as soon as 2027.

The massive wastewater recycling plant proposed for Southern California cities has also gained momentum in recent years due to dry conditions across its two key water sources, the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado River Basin. And Southern California is getting some funding help from its neighbors.

Water agencies in Arizona and Nevada are helping to pay for Metropolitan’s project in exchange for to-be-determined slices of Metropolitan’s Colorado River supply. The proposed plant would be built in Los Angeles and could produce up to 150 million gallons of potable water a day, or enough to serve more than 500,000 households.

If the rules are approved by California’s State Water Resources Control Board, the regulations would take effect once the state’s Office of Administrative Law signs off, which would likely happen by next summer or fall. From there, Metropolitan would be able to present its plans to the board for approval.

The Yuck Factor

Water agencies are moving swiftly to bolster their scarce Colorado River supplies with recycled water, but first, they must convince customers and politicians that drinking water originating from sewage is safe and worth the treatment cost.

A strong majority of respondents to an Arizona state survey said they would be “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to drink recycled wastewater.

Overcoming the so-called “yuck factor” could be a challenge for some utilities, though a recent direct potable reuse survey by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality found an appetite for the technology. A strong majority — 70 percent of respondents — said they would be “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to drink recycled wastewater. Some of the more skeptical responses included, “It sounds miraculous, but I would be suspicious,” “How will it taste?,” and “Is it safe for pregnant women?”

Phoenix’s Prieto said the city is crafting a public relations blueprint and giving presentations about the technology to a variety of different business and community groups. He said the initial response has been mostly positive.

“Some people thought we were already doing [direct potable reuse],” he said. “We’re hopeful that we can gain the public’s support and that they will see its safe and the best quality water provided anywhere in the city.”

Beer is another tool being used to overcome the yuck factor.

Lucrative craft beer competitions have been held in Arizona that require participants to use recycled wastewater, while Pima County has created a mobile trailer that treats effluent on site at breweries and provides clean water for brewing. Several Arizona and California breweries are now selling beer made with wastewater.

Once Arizona and California approve direct potable reuse regulations, water suppliers will have to figure out how to fund the technology.

Phoenix estimates its Cave Creek project will cost approximately $300 million and that a larger regional plant could cost more than $2 billion.

The final price tag for Metropolitan’s project could top $4 billion by the time it’s finished. Both water suppliers are hoping to tap into state and federal grants to offset some of the cost to their ratepayers.

Major cities are likely to become the first adopters of the technology, but the goal is for rural towns to eventually implement it as well.

Recycled water could be a solution in areas that are burdened by poor groundwater quality or those that don’t have access to surface water. The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality said interest in the technology has broadened to smaller cities.

While adopting the recycling technology isn’t cheap, creating a new water source that alleviates pressure on both the Colorado River and aquifers may be priceless.

“It’s one of the biggest and most important tools,” said Sorensen, who is now director of research at the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University. “It is absolutely critical to our water future.”

'Black Swans' are highly improbable events that come as a surprise, have major disruptive effects, and that are often rationalized after the fact as if they had been predictable to begin with. In our rapidly warming world, such events are occurring ever more frequently and include wildfires, floods, extreme heat, and drought.

'Green Shoots' is a term used to describe signs of economic recovery or positive data during a downturn. It references a period of growth and recovery, when plants start to show signs of health and life, and, therefore, has been employed as a metaphor for a recovering economy.

It is my hope that Black Swans / Green Shoots will help readers understand both climate-activated risk and opportunity so that you may invest in, advise, or lead organizations in the context of increasing pressures of global urbanization, resource scarcity, and perils relating to climate change. I believe that the tools of business and finance can help individuals, businesses, and global society make informed choices about who and what to protect, and I hope that this blog provides some insight into the policy and private sector tools used to assess investments in resilient reinforcement, response, or recovery.